Anna Gregor

you can't See a Painting on a screen

Anna Gregor

Selected Paintings

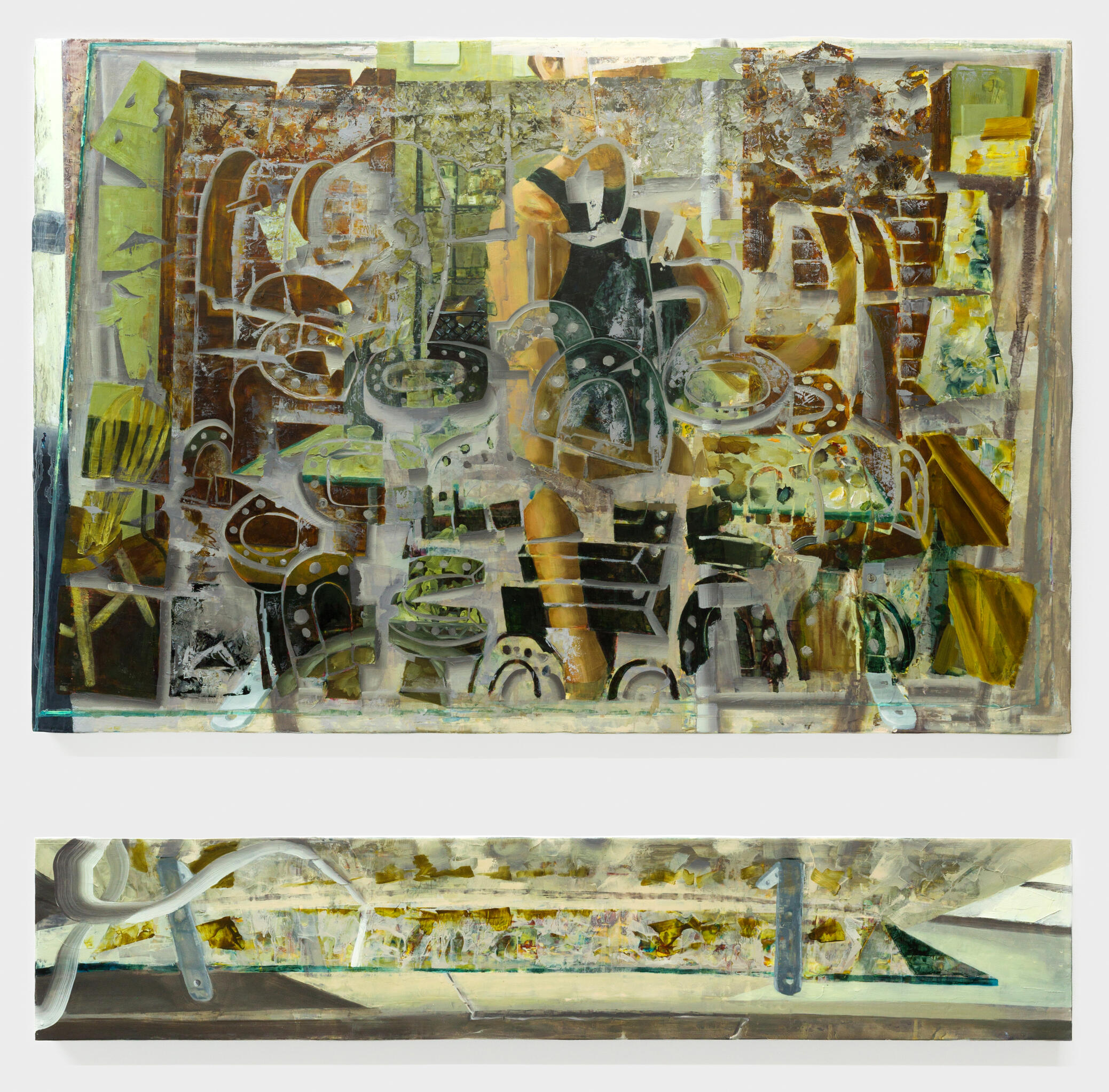

Figured Ground, 2025. Egg tempera, shellac, and oil paint on panels. 31 5/8 x 21 1/8" (top) 31 5/8" x 6 1/8" (bottom).

The Studio, 2025. Egg tempera, shellac, and oil paint on panel. 9 3/4 x 7 5/8".

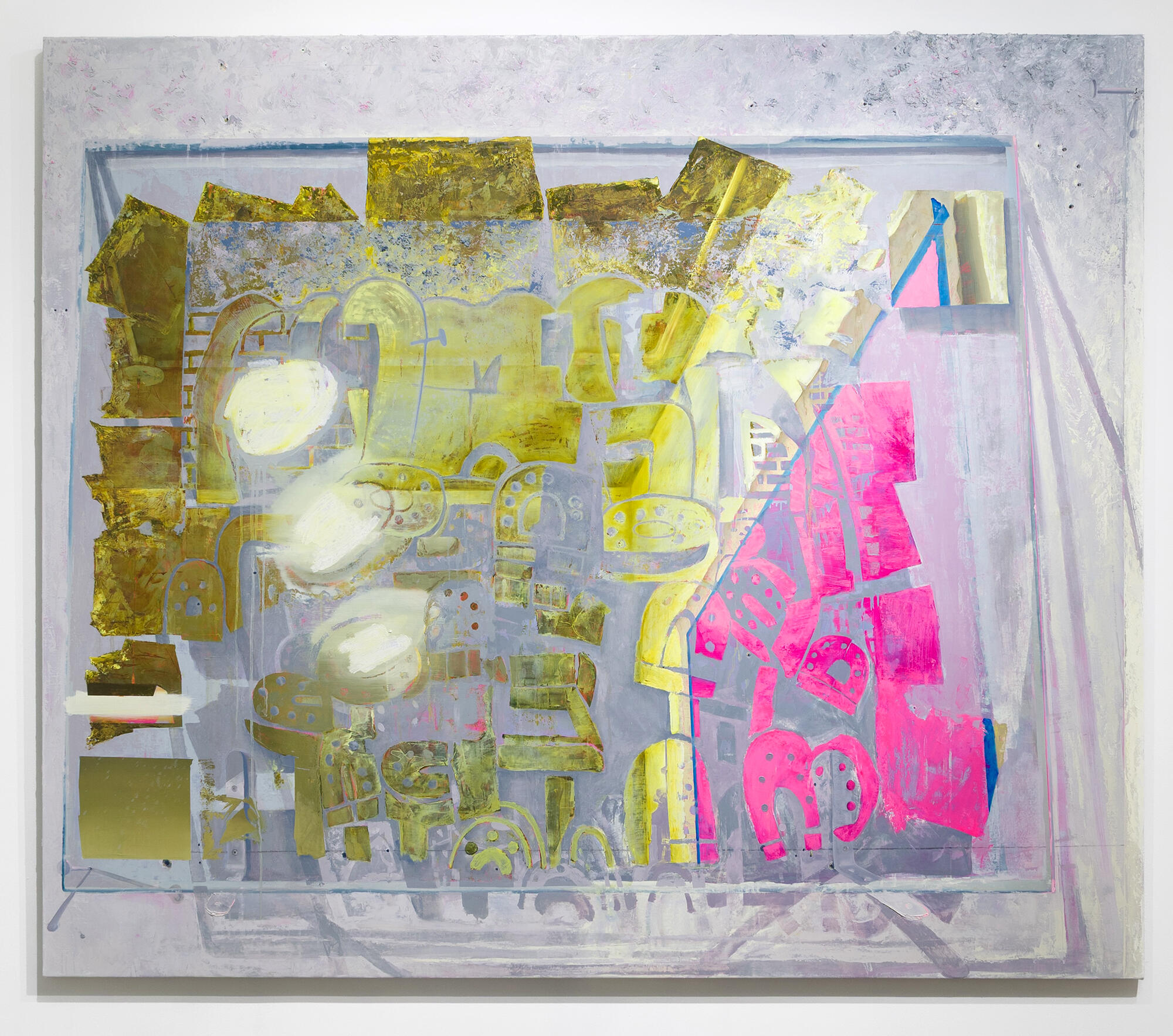

After Ancient Wall, 2025. Oil paint on canvas. 78 x 90".

After Ancient Wall, 2025. Oil paint on canvas. 78 x 90".

After Berlinghiero II, 2025. Oil paint on canvas. 88 x 58".

After Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 2025. Oil paint on canvas. 88 x 144.5".

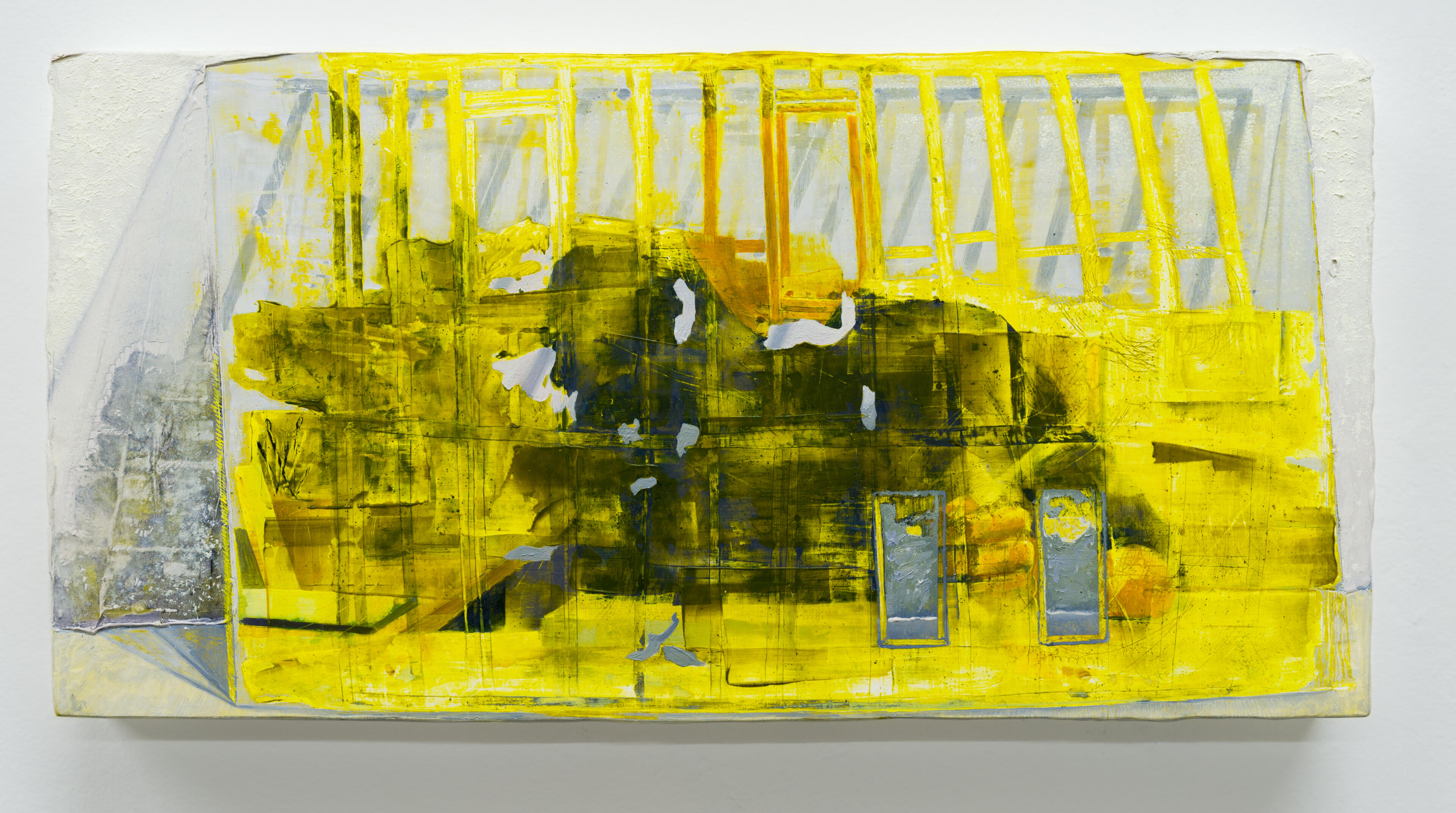

After Newman I, 2025. Egg tempera and oil paint on panel. 10 5/8 x 24".

Studio Reflected in Gold Mirror I, 2024. Oil on panel. 14 x 11"

After Fra Angelico (To What Can I Pray?), 2024. Oil paint on canvas. 14 x 11".

Hodegetria, 2024. Oil paint on canvas. 14 x 11".

Windowless Monad, 2024. Oil paint, rabbit skin glue, marble dust, muslin on panel. 6 x 12"

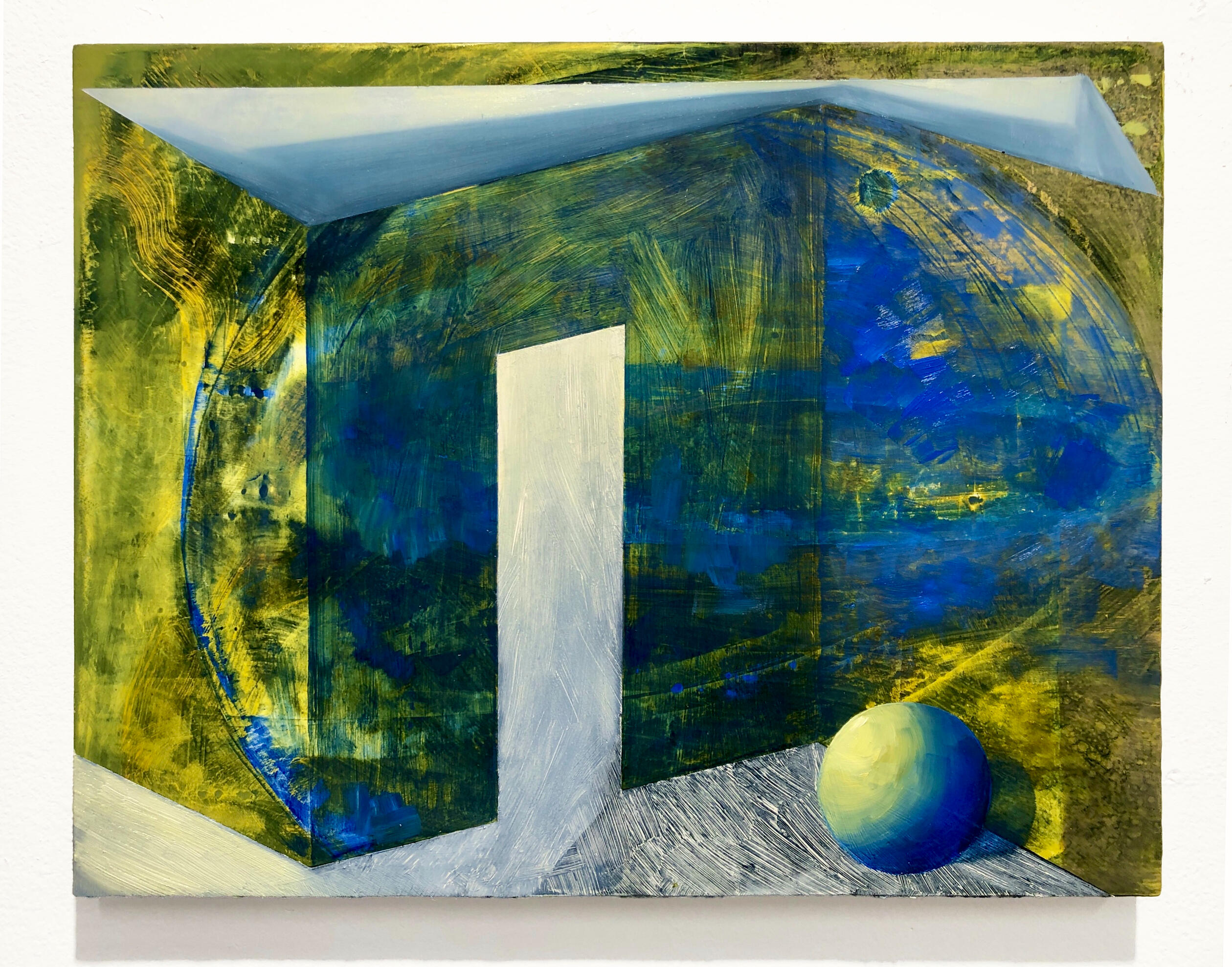

Cloister, 2024. Oil paint, rabbit skin glue, marble dust, muslin on panel. 5 x 7".

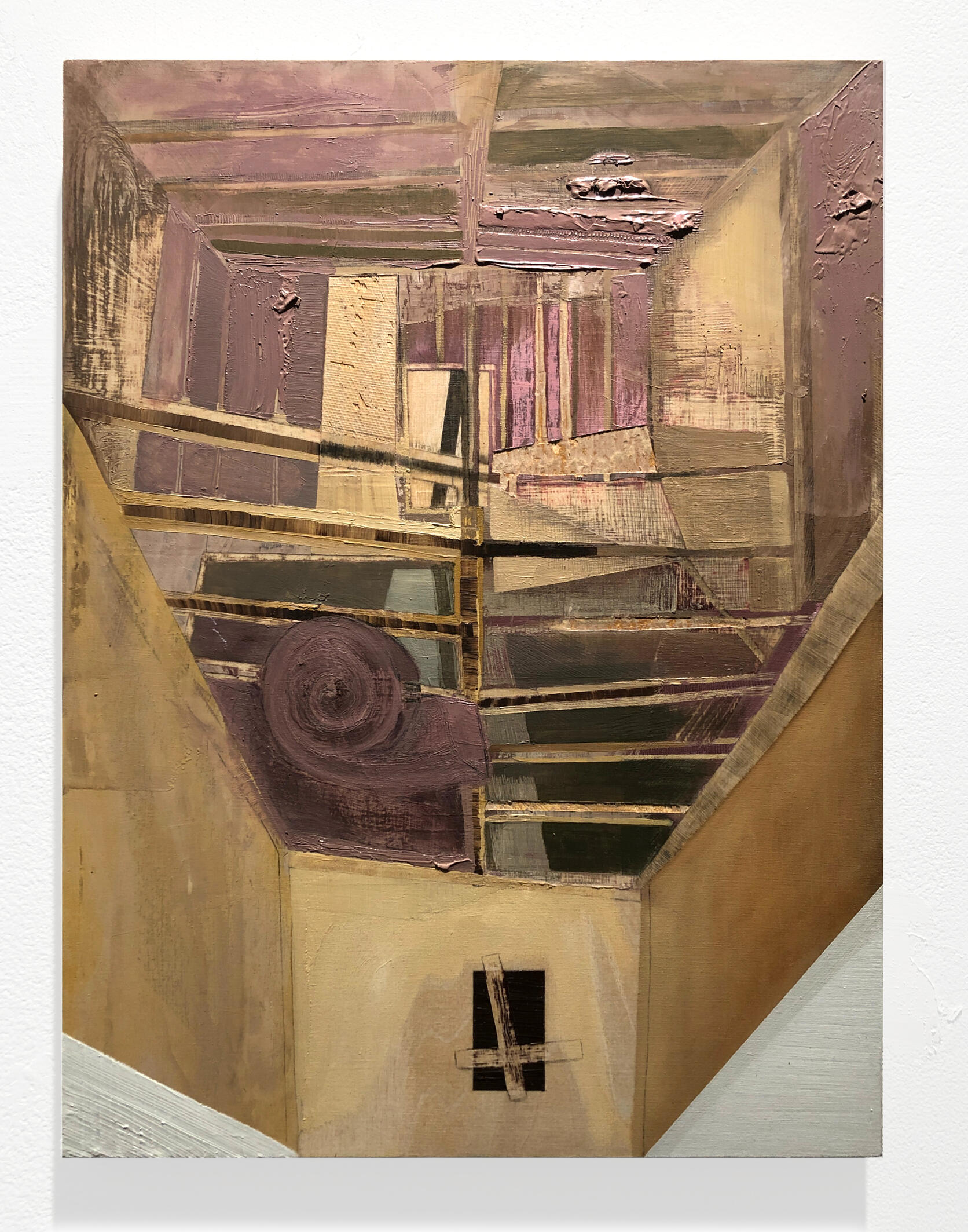

Double Space, 2024. Oil paint, rabbit skin glue, marble dust, muslin on panel. 36 x 24".

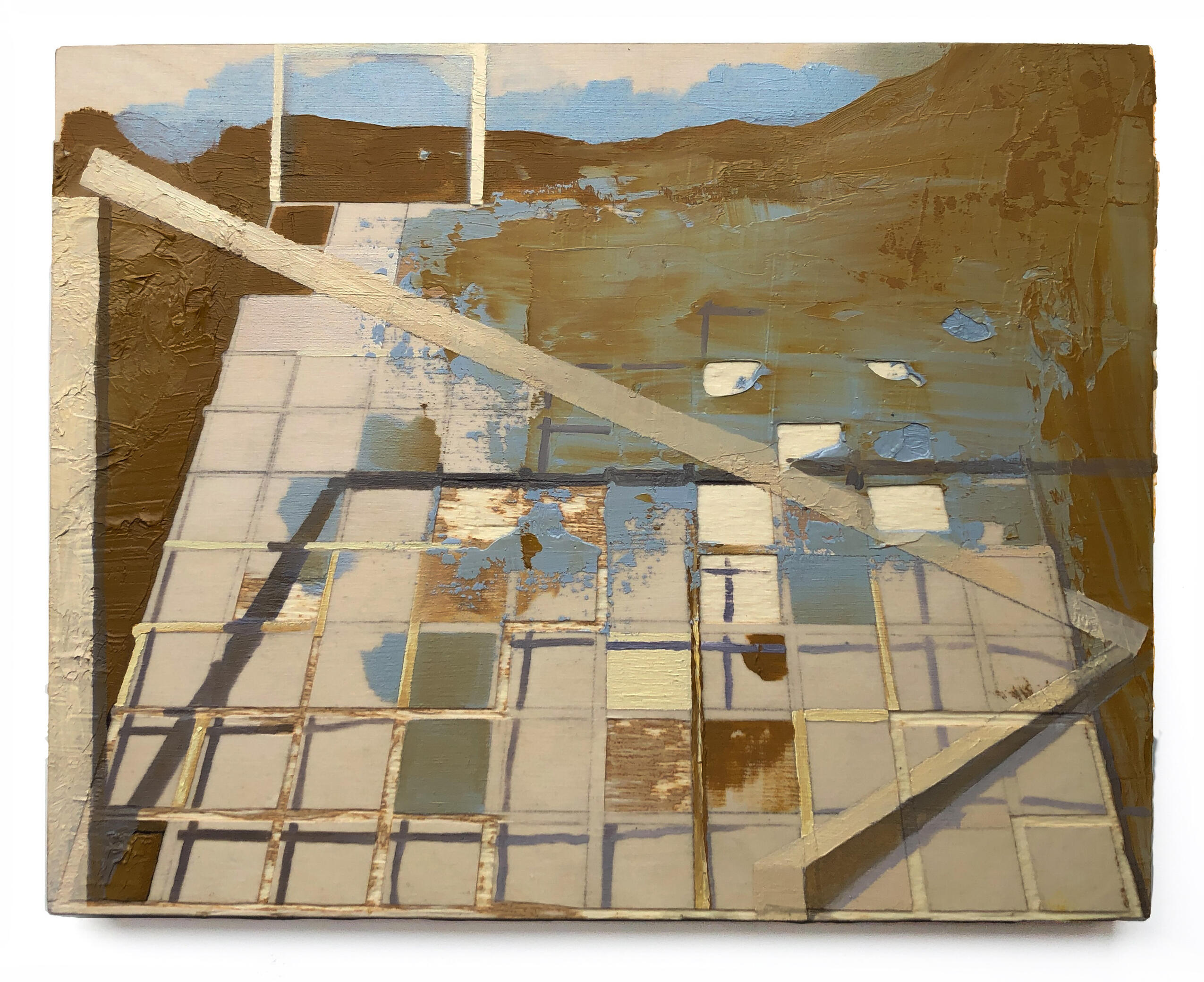

The Other Side, 2023. Oil paint on panel. 9 x 12".

Does This Painting Make Me Look Flat?, 2023. Oil paint on panel. 9 x 12".

Insulation, 2022. Oil paint on panel. 14 x 11".

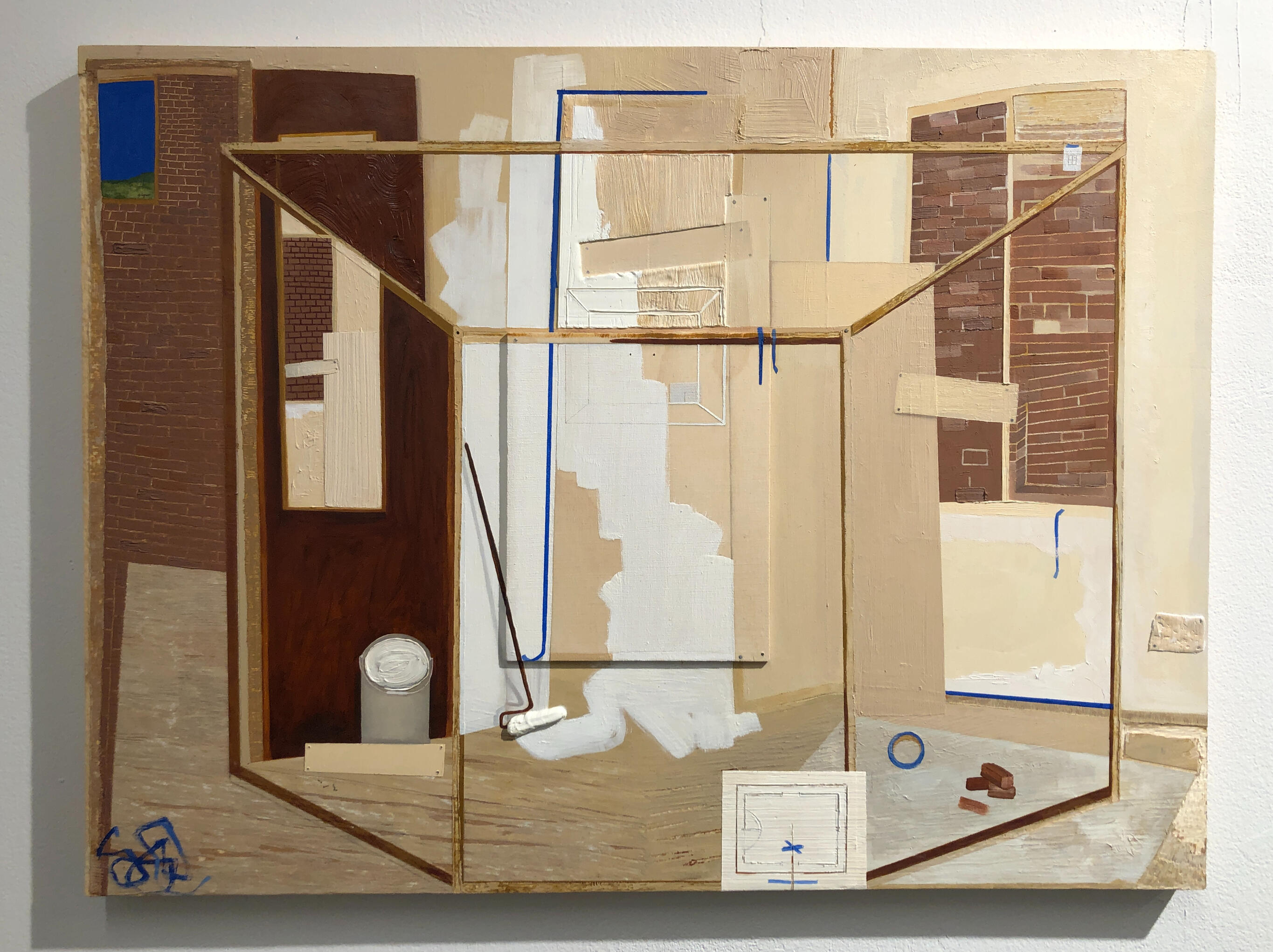

Escape Attempt, 2022. Oil paint on panel. 18 x 24".

Caution, 2022. Oil paint on panel. 9 x 11".

Faulty Foundation 4, 2022. Oil paint on panel. 9 x 11".

Faulty Foundation 3, 2022. Oil paint on panel. 9 x 11".

Faulty Foundation 1, 2022. Oil paint on panel. 9 x 11".

Medium, 2022. Oil paint on canvas. 36 x 48".

No Light Outside, No Light Above, 2022. Oil paint on canvas. 42 x 24".

Mimesis, 2021. Oil paint on clayboard. 8 x 10".

Stitches, 2021. Oil paint on panel. 20 x 16".

Crossing the Line, 2021. Oil paint on panel. 20 x 16".

Assimilation, 2021. Oil paint on panel. 14 x 11".

Wittgenstein's House, 2021. Oil paint on panels (diptych). 14 x 22"

Conversion 1, 2020. Oil paint on panels (diptych). 14 x 22"

Conversion 2, 2020. Oil paint on panels (diptych). 14 x 22"

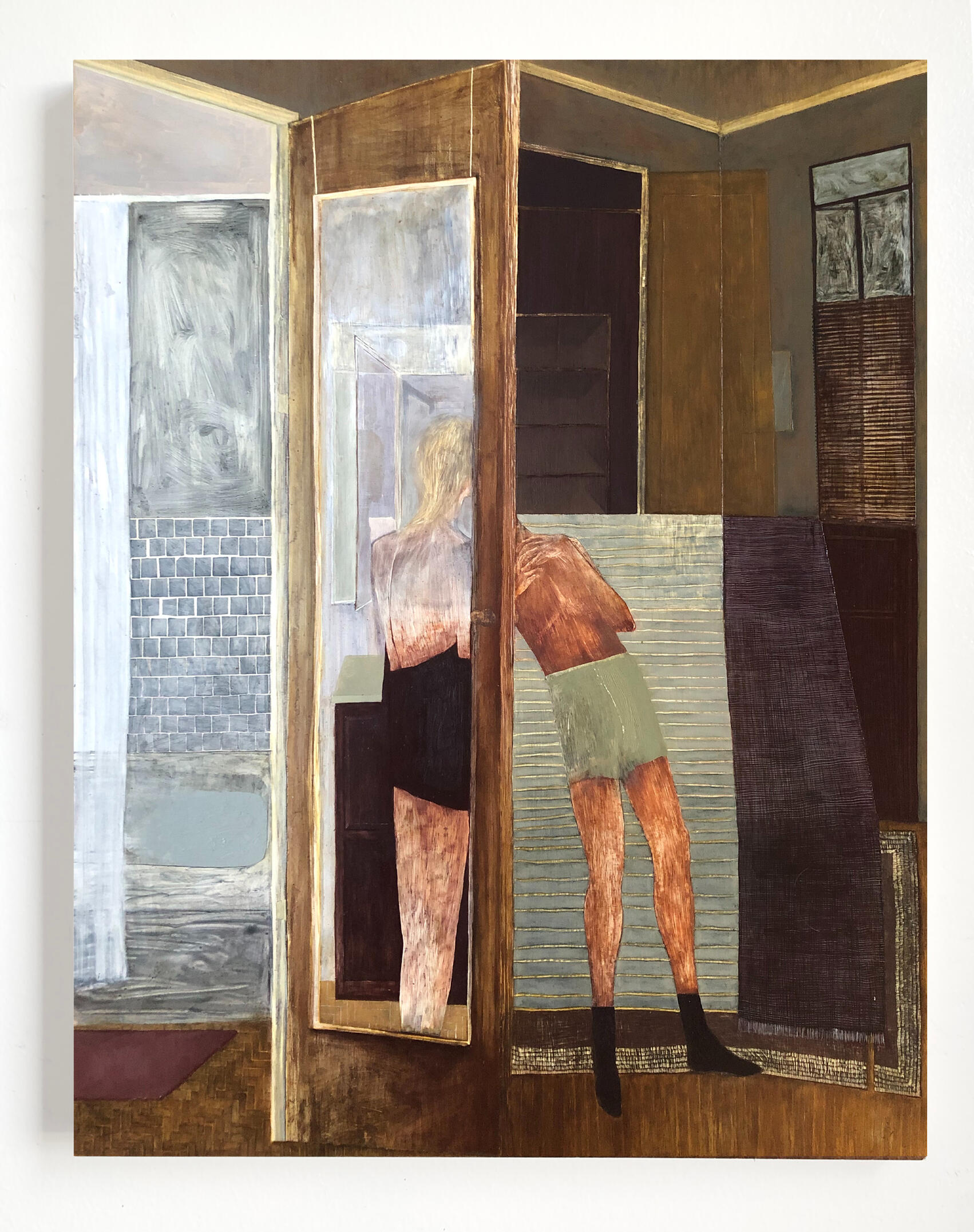

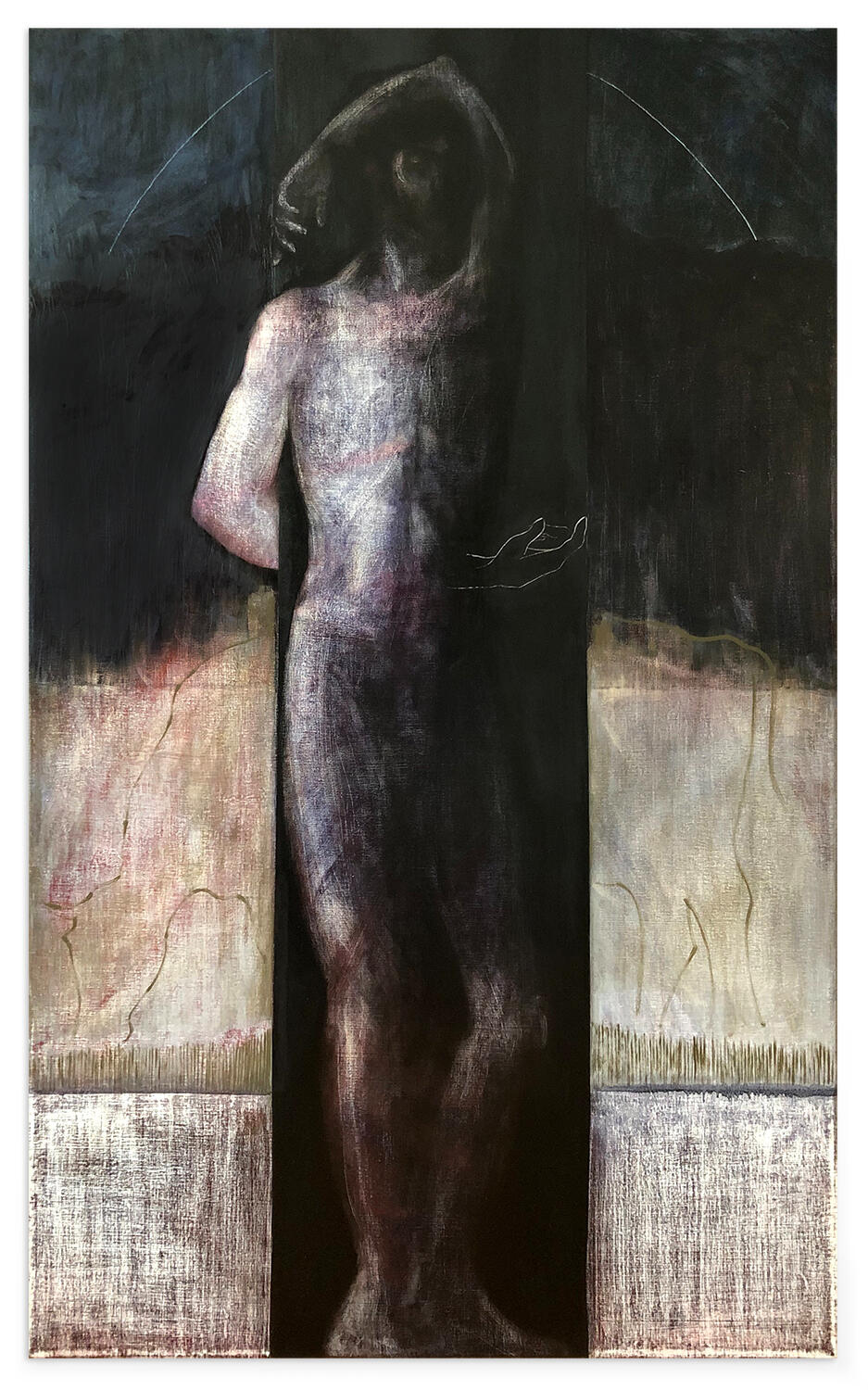

Animal, 2019. Oil on canvas. 55 x 33"

Anna Gregor

CV

EDUCATION

2022 - 2025 | MFA Painting, CUNY Hunter College, New York NY

2016 - 2019 | BFA Fine Arts, Parsons School of Design, New York NY

2012 - 2014 | Chemistry, Occidental College, Los Angeles CASOLO SHOWS

2024 | After Faith, Tomato Mouse at Art on Paper, New York NY

2024 | Double Space, D.D.D.D. Pictures, New York NY

2023 | Visions and Revisions, Moira Fitzsimmons Arons Art Gallery, Hamden CT

2022 | Embodiments, Tomato Mouse, Brooklyn NYTWO-/THREE-PERSON SHOWS

2026 | From that which is below, Tops Gallery, Memphis Tennessee (Upcoming Jan. 2026)

2025 | Till Human Voices Wake Us, Duckworth Gallery, Brooklyn NY

2025 | When Air Turns to Fog, Below Grand, New York NYGROUP SHOWS

2026 | Why Paint? II, Washington Studio School, Washington DC

2025 | Canvas Current, Emanuel von Baeyer London, London UK

2025 | World Animal, Hunter MFA 205 Hudson Gallery, New York NY

2024 | I Split the Dream, Neptune in June at Studio 9D, New York NY

2023 | Why Do Nymphs Turn into Trees, SPRING/BREAK Art Show 2023, New York NY

2023 | Homebodies, Unit London, Online

2023 | The Mind Roams as the Moth Roams, St Joseph’s University, Brooklyn NY

2022 | SPRING/BREAK Art Show 2022, New York NY

2022 | Among Friends, NY Artists Equity Association, New York NY

2022 | Intimacies, MAPSpace, Port Chester NY

2021 | SPRING/BREAK Art Show, New York NY

2021 | Chasing Light, Gallery 263, Cambridge MA

2021 | Double Vision, Bromfield Gallery, Boston MA

2021 | Storylines, Gallery 263, Cambridge MA

2021 | Fresh Perspectives Group Exhibition, London Paint Club, londonpaintclub.com

2020 | 2020 Members Invitational, NY Artists Equity Association, New York NY

2020 | Night & Day, Local Project Art Space & Departure Studios Gallery, Queens NY

2019 | Art 52nd Street 2019, Gallery MC, New York NY

2019 | Gregor, Huang, Karjalainen: Three Painters, 367 Gallery, Brooklyn NY

2019 | BFA Thesis Show, Parsons School of Design, New York NY

2019 | Public Privacy, The New School’s Skybridge Gallery, New York NY

2019 | Beyond Landscape, 25 East Gallery at Parsons School of Design, New York NY

2019 | Milk Press Books, New York Poetry Society, New York NYPRESS

2025 | The Treasure Below Grand, Jan Dickey for ArtSpiel

2025 | The Hunter MFA Show Is One of the Best Shows of the Year, Lisa Yin Zhang for Hyperallergic

2024 | These Are the Buzziest Artists Discovered at New York Art Week, Paul Laster for Galerie Magazine

2024 | Anna Gregor in the Retracted Age: A Conversation, Whitehot Magazine

2024 | Double Space at D.D.D.D., Art Spiel

2023 | Édouard Vuillard and the Context of Representing Domesticity, Rose Pickering

2022 | Embodiments: Critical Introduction, Eric Bayless-Hall

2022 | Emerging Artist Feature, E66 Studios

2021 | Issue 3, Huts Magazine

2021 | Artist to Watch, Art Connect

2020 | Human Nature, Vellum Magazine No. 24

2019 | Gregor, Huang, Karjalainen: Three Painters by Eric Bayless-HallAWARDS + FELLOWSHIPS

2025 | Masters Thesis Grant, CUNY Hunter College

2024 - 2025 | Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation Grant

2022 - 2025 | Ruth Stanton Scholarship, CUNY Hunter College

2021 | AltMFA Fellow, The Crit Lab

2019 | Social Science Fellowship, The New School

2019 | Global Ambassador, The New School

2018 | Opportunity Award Recipient, The New SchoolTEACHING

2025-2026 | Assistant Adjunct Professor, Undergraduate Beginning/Advanced Painting, CUNY Hunter College

2025-2026 | Assistant Adjunct Professor, Undergraduate Drawing I, Fordham University

2023-2025 | Art Teacher, Fusion Academy Upper West Side

2023 | Teaching Assistant, Undergraduate Beginning/Advanced Painting, CUNY Hunter College

2019-2021 | Teaching Assistant, Art Theory and Aesthetics Courses taught by Prof. Arnold Klein, Parsons The New School for Design’s Department of Art and Design History and TheoryCOLLABORATIONS

2019 | Translation/Transmigration, Matthew Gallery, New York NY (reading based on film made in collaboration with Tatiana Istomina)

2018 | Philosophy of the Encounter: Screening, Triangle Arts Association, Brooklyn NY (film in collaboration with Tatiana Istomina)

Anna Gregor

Essays

- Alla Prima Amnesia: Phoebe Helander at PPOW, Perseity Art Review (2026)

- Two Worlds Aflame: Corot's The Burning of Sodom, Painters on Paintings (2026)

- The Art Critics Who Don't Want Better Art, Two Coats of Paint (2025)

- paintings and Paintings, Caesura Magazine (2025)

- Raoul de Keyser: The Dialectical Freedom of Painting, Caesura Magazine (2025)

- Cattelan’s Comedian: Subjectivity and the Possibility of Sharing a World In the Art-Judgment, The Revenant Quarterly (2025)

- A Lesson in Art at Duckworth Gallery, Two Coats of Paint (2025)

- Ian Meyers: A Painter's Faith, Two Coats of Paint (2024)

- Aggregate: The City as Nature, Two Coats of Paint (2024)

- C’Naan Hamburger: Vanitas, Whitehot Magazine (2024)

- A Disposition to Look, s(S)eeing p(P)aintings (2023)

- Tess Wei: Seeing the world through dirty snow, Two Coats of Paint (2023)

- Problematic Experience: Recognition, Reflection, and Responsibility in Art, The Revenant Quarterly (2022)

- On Embodiments, The Revenant Quarterly (2022)